News

Arts & Crafts & Design

April 2014 issue, page 50-55

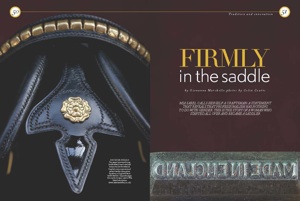

FIRMLY IN THE SADDLE

by Giovanna Marchello

photos by Colin Coutts

Mia Sabel calls herself a craftsman: a statement that reveals that professionalism has nothing to do with gender. This is the story of a woman who started all over and became a saddler.

“I call myself a craftsman,” Mia Sabel tells me as we reach her workshop, an airy log cabin at the back of her big and overgrown garden in Walthamstow, East London. What strikes me about her statement is that she neither uses the feminine “craftswoman” nor the neutral “craftsperson”. As the conversation unwinds, I understand that the term with which she chooses to define herself reveals the pride and self-confidence

of a person who, having built a successful career, turned the tables halfway through her life and dedicated herself to learning a skilled craft. Mia Sabel became a qualified saddler at the age of 44, a process that requires time, commitment and practice as well as a manual dexterity that is normally trained at a younger age. And, as her story demonstrates, professionalism has nothing to do with gender, but with one’s approach, attitude and conscientiousness. Likewise, she believes that the right word is necessary

when it comes to setting the crafts to rights. “In the UK, most consumers will probably associate the word ‘craft’ with home-made knitted scarves, doilies and all the rest. But when we talk about high-end craftsmanship, we refer to a craft that takes three to four year’s training or an apprenticeship of four years. Often, ‘amateur craft’ and ‘professional craft’ are merged together, and it’s a shame. There’s nothing wrong with being an amateur, but this difference has to be understood. I think it is important, because it has to do with what the consumer perceives.”

The mixture and degree of tradition, creativity, skill, experience, sophistication and innovation that elevates a craft to the heights of métier d’art is not easy to define. This issue and, more in general, the characteristics

and role of the crafts industry in the contemporary economy are, as we know, at the centre of great interest and debate throughout the Western world. In the UK, crafts and craftsmanship are supported and endorsed by renowned and influential national non-profit associations and agencies, among which the most important are the

Crafts Council, which is focused on contemporary crafts and receives public funding through Arts Council England, and the Heritage Crafts Association, the advocacy body for traditional heritage crafts presided by HRH The Prince of Wales, which supports the application of the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Both associations have taken an active role in the controversy arisen last year when the British Department

for Culture, Media and Sport opened

a public consultation regarding the classification and measuring of the creative industries, from which the category of crafts was running the risk of being deleted. In fact, in its latest report on creative industries issued in April 2013, the DCMS provided no figures

for the contribution of crafts to creative

industries. After a public outcry that led to petitions and lobby action, the Government clarified its position and officially confirmed through its web site that “the definition of the creative industries will remain the same and continue to include crafts.”

“In my previous job, I would have completely fallen into the creative industries area, because I was a designer and a creative director, and probably this issue would not have touched me as deeply as in fact it did.”

Mia Sabel represents that growing proportion of men and women who have chosen a second career in the crafts. In her case, a third career. “At 17 I joined a youth theatre group for seven years, with which I toured the UK. It was a fundamental experience. I learned life skills as well as a profession: costume making, stage design, lighting, and computer. We had no funding, our profits came entirely from the shows we set up.” Although she had become a professional stage manager, at the age of 25 she decided to go back to college to study art and photography. She was accepted on a course at Central St. Martins School of Art, where she worked hard for three years and discovered she had a gift for computers and graphics culminating in a First Class Degree. So her second career started in the booming new technology world, where she worked as an animator, illustrator and web designer. In the course of the years she passed from a multinational digital agency to advertising and finally to creative director of an online bank, where she was managing a team of 22 creatives. She loved her job and the salary was excellent, but she was not satisfied: “I was working 16 hours a day, and I felt that the managerial side

was taking over the creative one. On top of that, ethical and moral issues were becoming more and more important to me, and I was starting to ask myself who I was and what I was doing.” So she left, and went to Spain to learn the language and ride horses. “I wanted to clear the decks. After that experience, I understood that I needed to do something creative and physical, to be out in the open air with horses and produce objects that would outlive me. Like the things my grandfather, a master carpenter, made for us in the course of his life.”

Mia Sabel wanted to learn a trade and craft that had tradition, history and a cultural heritage, and she chose saddlery. She enrolled at Capel Manor College, which provides the only full-time, two-year course in the country. “Only twelve students are taken every year. Under the tuition of a Master Saddler, we learned the very traditional

methods of English saddlery, that includes saddles, bridles and harnesses, as well as the anatomy and physiology of horses. The exams are very skills-based, testing core competencies and accuracy in a given amount of time. Once you have qualified, which counts as an apprenticeship, it takes at least another three years of working in the trade to qualify for an application as Master Saddler. It used to be a very masculine trade, but in the classroom women are definitely outnumbering men.” The making of a saddle involves many different skills, and everything starts from the horse. “The upholstery of the saddle, the wooden body called the tree, depends on the size and type of the horse and on the use for which a particular saddle is intended: dressage, racing, jumping, polo and so on. The saddler works on the saddle to fit it to the horse and to suit the customer’s requirements. A very laborious, physical work. The leather for the seat is wet-moulded on the tree and laboriously hand-stitched. The panels, the lateral pads that touch the horse’s sides, are shaped to suit the horse and flocked with wool and adjusted according to the balance of the saddle, which should be checked by a qualified saddle fitter every six months.” Leather was her language, and her creative side was coming back to her. In her third year she approached QEST, the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust, which makes awards to craftsmen and women of all ages for study, training and work experience. “It’s an amazing charity. Once you become a QEST scholar, you are a scholar for life, with fantastic opportunities to do many things. I was granted a scholarship to complete my saddlery qualifications and widen my skills to include bag making, restoration and upholstery. The more I learned, the more I offered, combining my new skills with my design background.” Mia Sabel doesn’t do much saddlery now. “It’s very difficult and there is a lot of competition. It’s very hard to get someone to pay for a completely hand-made saddle. I still do repairs, because it’s a fantastic way to learn how things work and find solutions to fix them. I also do prototyping. I work a great deal with specialised companies who want me to research and develop bespoke products for them. I also work with architects and designers, to develop their ideas in leather. And of course I create my own luxury leather line, for which I often use bridle leather, the strongest and toughest. I use the typical colours of saddlery, which go from naturals to brown, black and red. I can do pink of course, if a customer asks, but in my collection I like to focus on tradition.” Her signature item is the Stirrup Bag, which she invented for her product range. Mia Sabel tells me that when Queen Elizabeth II saw it, on an official visit to the QEST Crafting

Excellence exhibition held at Fortnum and Mason in 2012, she picked it up with her gloved hand and said she was impressed by how light it was. A very encouraging debut for a craftsman who has one ambition: to make the best and most beautiful objects for the most sophisticated customers.

Mia Sabel has integrated her new competencies with her previously acquired skills and technological fluency, building a bridge between heritage and contemporary crafts, and amplifying the range of her reach beyond traditional boundaries. But like many modern craftsmen who do not fit in classical definitions, she has to improvise and open her way inch by inch into a rapidly changing world in which the institutions and the industry are not running at the same pace. The 21st century craftsman must also be an inventor, an explorer and a guerrilla fighter.